Taste

Plant Parts Used

Therapeutic Properties

Ayurvedic Character

Cooling

Current Uses

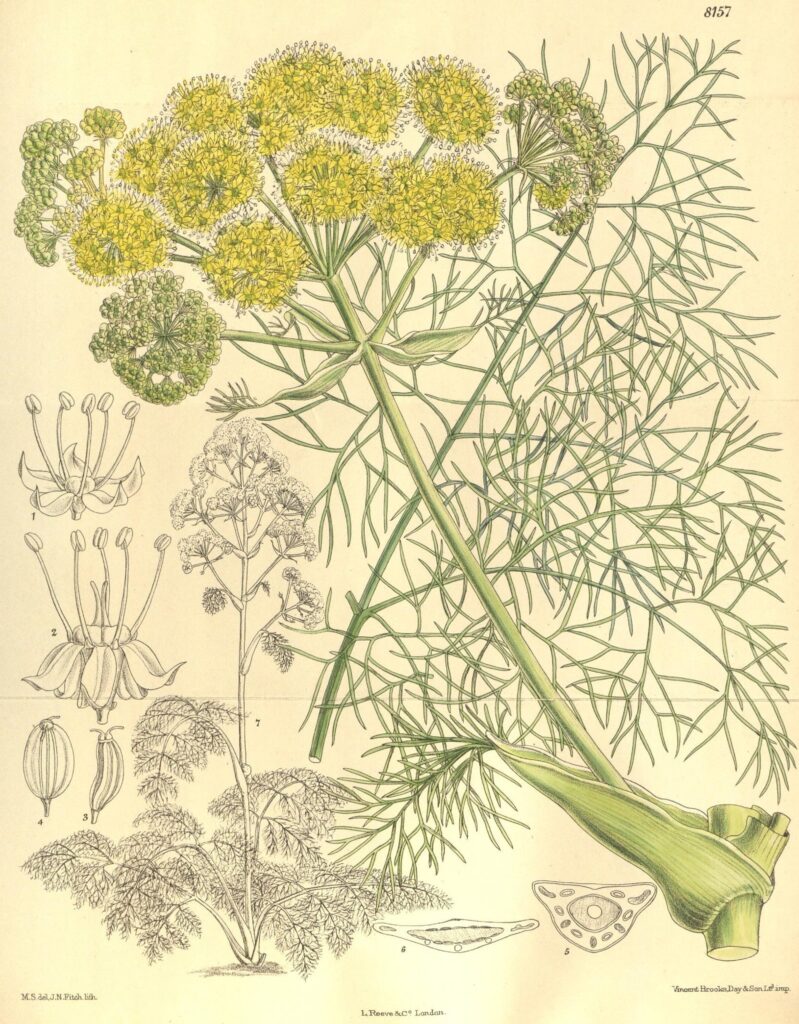

If you work behind a bar, you already know fennel’s flavor even if you’ve never handled the plant itself. The dried seeds are a cornerstone botanical in absinthe, pastis, sambuca, aquavit, and a long list of amari and bitters, where they lend a sweet, cooling anise note that softens aggressive bitterness. In spirits, fennel acts like a bridge, smoothing the gap between harsh roots, barks, and gentler citrus peels while adding aromatic lift.

Outside the bottle, fennel seed shows up everywhere from sausage and rye bread to Indian after-dinner mukhwas. Traditionally, it has also been chewed plain as a digestif. That dual culinary–digestive role explains why fennel has remained a favorite in liqueurs meant to be sipped slowly after a meal.

Precautions

Fennel is generally regarded as safe in culinary and beverage amounts. Concentrated fennel essential oil should be used cautiously, as excessive intake can cause nausea or neurological effects. People with known sensitivities to plants in the Apiaceae family should proceed carefully.

Substitutions

Anise seed is the closest swap, though it is sharper and more overtly licorice-forward. Star anise can stand in at lower quantities, but it is more intense and woody. Caraway offers digestive support and aromatic warmth, but with a savory, earthy profile rather than fennel’s sweetness.

History

Origins

Fennel’s relationship with digestion goes back to antiquity. Ancient Greeks and Romans used it as both food and medicine, valuing it for its ability to “open” obstructions and settle the stomach. Dioscorides described fennel as warming and dispersing, particularly helpful after heavy meals, while Pliny the Elder praised it for sharpening vision and easing digestion.

During the Middle Ages, fennel became a common monastic garden plant across Europe. It was hung over doorways to ward off ill fortune and brewed into cordials to counter rich, meat-heavy diets. By the time distillation took hold, fennel naturally found its way into spirits designed for the gut, cementing its place in Europe’s digestive drinking culture.

Footnotes

- Culpeper, Nicholas. Culpeper’s Complete Herbal. London, 1653.

- Dioscorides. De Materia Medica. Translated by Lily Y. Beck, Olms-Weidmann, 2005.

- Hoffmann, David. Medical Herbalism: The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Healing Arts Press, 2003.

http://images.cdn.fotopedia.com/flickr-309381758-original.jpg