Taste

Plant Parts Used

Therapeutic Properties

Ayurvedic Character

Heating

Current Uses

Basil might be one of the world’s most familiar herbs in the kitchen, but behind the caprese salads and Negronis lurks a plant with far more depth than its bright, peppery aroma suggests. In mixology, fresh basil leaves lend vibrant green notes to cocktails, playing well with citrus, berry, and gin-forward builds. They show up in everything from refreshing garden sours and basil Gimlets to more adventurous bitters and macerated liqueurs. Muddling is classic, but infusion—into syrups, vermouths, or neutral spirits—coaxes out subtler, spicier undertones you’d miss with fresh garnish alone.

Beyond the bar, basil is increasingly appreciated for its adaptogenic and digestive virtues. Herbalists and bartenders alike use it to stimulate appetite and lighten the load on the gut, especially when meals and drinks lean heavy. A touch of basil can lift an amaro blend or round out bitter-forward aperitifs with its aromatic balance. Think of it as the herbal bridge between bright top notes and grounding bitter roots—a balancing act that keeps botanical blends from veering too austere or cloying.

Precautions

Basil is generally considered safe in culinary and beverage amounts. However, concentrated essential oil should be used sparingly and with caution, as large doses may be toxic. Some varieties contain small amounts of estragole, a compound with potential carcinogenic activity in high concentrations1.

Substitutions

If fresh basil isn’t available, tulsi (holy basil) offers a more pungent, clove-like depth with added adaptogenic punch, while shiso brings a brighter, citrusy-green lift. Tarragon or lemon balm can also approximate basil’s volatile, fresh character in drinks or infusions.

History

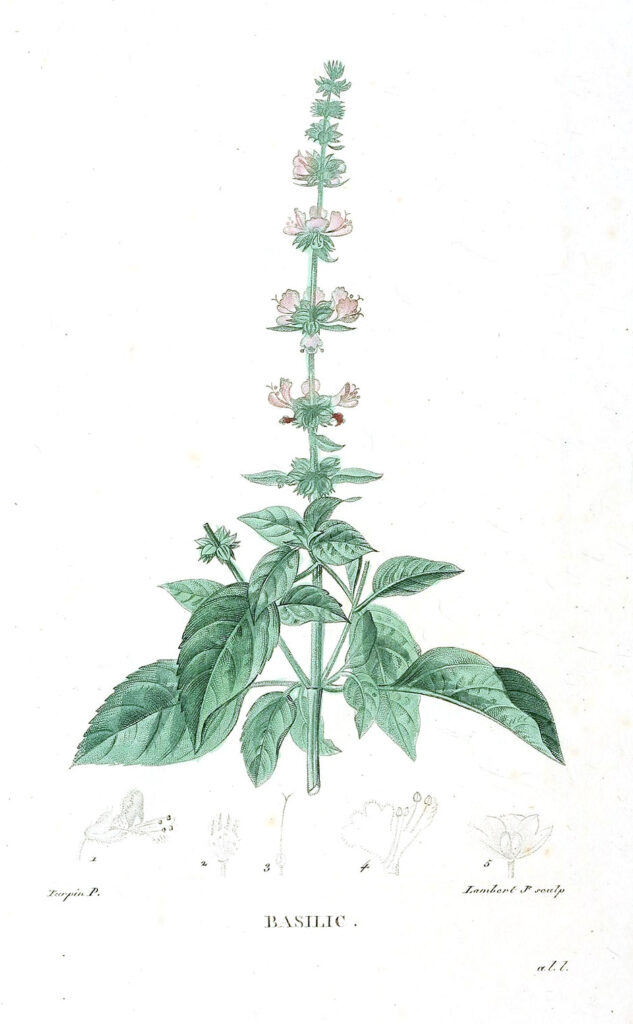

Basil (Ocimum basilicum) has been revered and reviled in equal measure for millennia. Native to tropical Asia and Africa, it was cultivated in ancient India over 3,000 years ago, where it was valued for its sacred and medicinal qualities2. Greeks and Romans associated it with love and fertility, though Pliny the Elder noted its supposed power to provoke madness if sniffed too often. In medieval Europe, basil was sometimes linked to scorpions and demons, while in Renaissance Italy it symbolized love and was tucked into courting bouquets3.

Its global spread mirrored the spice trade, and basil quickly adapted to local cuisines and remedies from the Mediterranean to the Caribbean. By the 18th century, it had found a permanent place in both kitchen gardens and apothecaries. Today, while it’s best known as a culinary staple, its role as a tonic, carminative, and aromatic remains part of herbal traditions from Ayurveda to European monastic medicine.