Taste

Plant Parts Used

Therapeutic Properties

Ayurvedic Character

Cooling

Current Uses

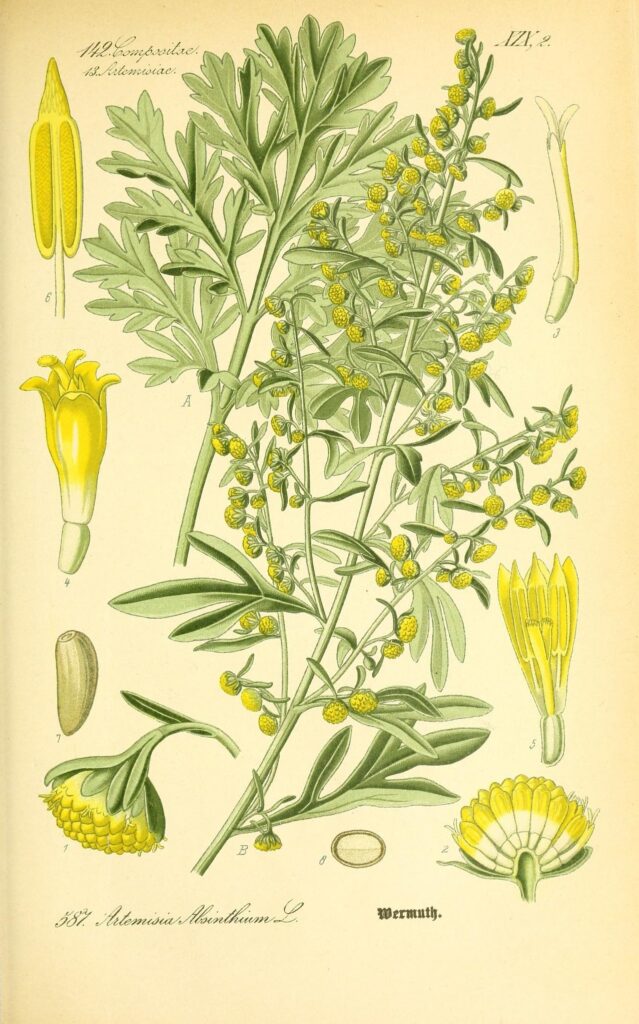

Few plants have a reputation as notorious — or as misunderstood — as wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). Bitter to the point of defiance, this silvery-green perennial has been used for millennia to rouse sluggish digestion, purge intestinal parasites, and steady the stomach after heavy meals. The Greeks and Romans steeped it in wine and called it a tonic for the liver, and medieval apothecaries prescribed it for everything from fevers to melancholy. Even today, its chief bitter compounds — absinthin and anabsinthin — are prized for stimulating gastric juices and bile production, which is why a sip of an aperitif or digestif containing wormwood still primes your appetite and settles your gut before or after a rich meal (Bone & Mills 2013, 83–84; Duke 2002, 57).

But let’s be honest — wormwood’s real fame comes from its role in absinthe, that myth-drenched spirit beloved by 19th-century bohemians and vilified by governments. Its active constituent thujone sparked centuries of controversy, blamed (wrongly) for hallucinations and madness until modern science debunked the hysteria. In reality, traditional absinthes contained only trace amounts of thujone — nowhere near enough to cause hallucinations — and the “green fairy’s” infamy likely stemmed more from overindulgence than from the herb itself (Lanier 2013, 52–54; Adams 2020, 118). Still, wormwood’s assertive bitterness gives absinthe and many classic vermouths and bitters their sharp, unmistakable edge, the kind of flavor that cuts through sweetness and commands attention.

If you’re working behind a bar, think of wormwood as both a historical anchor and a sensory tool. A few drops of a wormwood tincture or a well-chosen absinthe rinse doesn’t just nod to tradition — it transforms a drink. It wakes up the palate, deepens complexity, and connects you (and your guests) to centuries of herbal craft. It’s not a plant for the faint of heart, but that’s precisely its charm.

Today, wormwood’s bitter punch is most often harnessed in the world of spirits and herbal medicine. Behind the bar, it’s an essential component in absinthe, vermouth, and certain styles of bitters, lending an intense, clean bitterness that sharpens sweet or rich flavors and awakens the palate. Many bartenders also rely on wormwood tinctures or macerations to add depth and complexity to house blends or to use in micro-doses as cocktail accents — a few drops are all you need to transform a drink.

Beyond its spirited life, wormwood still earns its keep as a digestive ally. Its compounds, particularly absinthin and anabsinthin, are known to stimulate gastric secretions and bile flow, making it useful before meals to boost appetite or afterward to ease heaviness and bloating (Bone & Mills 2013, 83–84). It’s also used in traditional medicine as an anthelmintic — a remedy against intestinal parasites — and is sometimes included in herbal bitters formulas designed to “wake up” a sluggish liver (Duke 2002, 57).

Precautions

Wormwood should be used in moderation. Its thujone content can be toxic in large doses, causing nausea, seizures, or neurotoxic effects (Bone & Mills 2013, 83). Pregnant or breastfeeding individuals should avoid it, as should those with seizure disorders. Always source from reputable suppliers and avoid essential oils for internal use, which are highly concentrated.

Substitutions

If wormwood’s intensity isn’t to your liking or you can’t source it, milder Artemisia species like Roman wormwood (A. pontica) or mugwort (A. vulgaris) can substitute, though they offer softer bitterness. Gentian or quassia can also provide a bitter backbone, though their flavor profiles lack wormwood’s resinous, aromatic complexity.

History

Wormwood’s story is as old as medicine itself. Ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans all wrote of its virtues — Hippocrates prescribed it for menstrual pain and digestion, while Pliny the Elder described wormwood wine as a tonic for the liver and stomach (Lanier 2013, 12). In the Middle Ages, it was a staple of European apothecaries, used for fevers, parasites, and melancholy, and even tucked into bed linens to repel insects.

Its reputation, however, soared and soured with absinthe in the 19th century. Artists and poets from Van Gogh to Verlaine celebrated the “green fairy,” while moral reformers demonized it as a hallucinogenic menace. Thujone was blamed for madness and crime until early 20th-century bans swept across Europe and the United States. Science has since cleared wormwood’s name — traditional absinthes contained only trace thujone — and modern laws regulate safe levels, restoring the herb’s rightful place in spirits and bitters (Adams 2020, 118; Lanier 2013, 52–54).

Footnotes

Photo by: fotopedia

-

Adams, Jad. Hideous Absinthe: A History of the Devil in a Bottle. University of Wisconsin Press, 2020.

-

Bone, Kerry, and Simon Mills. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine. 2nd ed., Churchill Livingstone, 2013.

-

Duke, James A. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs. 2nd ed., CRC Press, 2002.

-

Lanier, Doris. Absinthe: The Cocaine of the Nineteenth Century. McFarland, 2013.