Current Uses

If there’s a flower that belongs behind the bar as much as in the garden, it’s borage. With its vivid blue, star-shaped blossoms and subtle cucumber flavor, this Mediterranean native lends a crisp, refreshing lift to summer cocktails. The petals make an elegant garnish in a gin and tonic, while the leaves—lightly fuzzy and cool on the palate—have long flavored lemonades and Pimm’s Cups in England. You’ll sometimes see borage flowers frozen into ice cubes or floated atop spritzes and tonics to add a touch of color and gentle vegetal perfume.

Beyond the glass, bartenders appreciate borage for the same reason herbalists always have: it’s uplifting. The plant’s fresh taste and delicate aroma have a cheering effect that complements light spirits like gin, vermouth, and floral liqueurs. Some modern amaro makers experiment with borage to add a clean green note that bridges citrus and spice, giving balance to bitters-heavy blends.

Precautions

While borage leaves and flowers are generally safe in modest culinary use, the plant contains small amounts of pyrrolizidine alkaloids, compounds that may be toxic to the liver in large or prolonged doses. Avoid internal medicinal use of borage oil or extracts unless they’ve been certified free of these alkaloids. Pregnant or nursing individuals should avoid concentrated forms.

Substitutions

If borage isn’t handy, cucumber peel or fresh cucumber juice gives a similar refreshing coolness. Hyssop or lemon balm can mimic some of borage’s floral-green brightness, especially in infused syrups or tinctures.

History

Origins

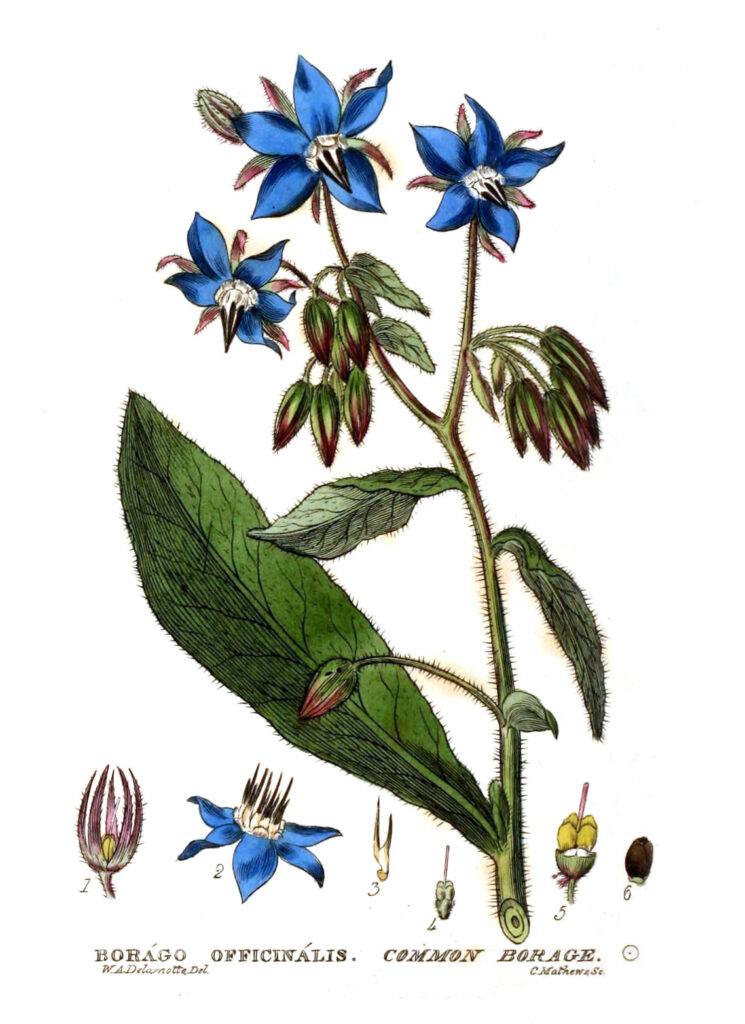

Borage has been cheering humans for over two thousand years. The ancient Greeks and Romans steeped its leaves and flowers in wine to “drive away sorrow and make men and women glad of heart,” as Pliny the Elder noted in Naturalis Historia¹. Medieval herbalists continued the tradition, calling it the “herb of courage.” Its Latin name likely comes from corago—meaning “to bring courage”—a nod to its reputation for brightening mood and relieving melancholy.

By the Renaissance, borage had made its way into monastery gardens and apothecaries across Europe, valued for cooling fevers and soothing nerves². In Elizabethan England, it became a common addition to cordial waters, and by the 19th century, it found its way into the classic Pimm’s Cup—cementing its place as a botanical with both medicinal and mixological charm.

Footnotes

-

Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historia, Book XXI, 77 CE.

-

Culpeper, Nicholas. The Complete Herbal, 1653.